Was It Real...or Was It Memory?

Was It Real...or Was It Memory?Memories are odd things. We've probably all had the experience of returning to a vividly-remembered place to discover it wasn't like that at all. Sometimes with the passage of time we begin to question whether some things we remember ever happened. That's what this post is about: a childhood memory so vivid that it's remained with me my entire life. Yet I've never found evidence that the remembered event happened. Even given my small group of followers, I'm hoping the magic of the Internet will finally give me an answer. That fantastic toy I lusted after one Christmas nearly 50 years ago..did it really exist? Or have I carried a false memory with me for half a century?

In the early 1960s I lived in a small Washington town called Snohomish (pop. 4000). The nearest large town was Everett (pop. 14,000). In Everett was a Sears store. Next to the main Sears building was a sort of annex. I think it served as the garden and hardware department for most of the year. But at Christmas it was transformed into a Toyland to dazzle the eyes and quicken the heart of any pre-teen boy or girl. Especially a boy. Toys were strictly gender-segregated and the boys got all the trains, bikes, airplanes, guns (of course), construction equipment, and spaceships. One special Christmas I saw a magnificent toy line that brought the last two items together: a group of futuristic building machines, like Tonka Toys from the 25th Century.

These were the days when Marx and Tonka sold big, ruggedly-built toys representing the era's construction equipment: earthmovers, caterpillar tractors, road graders, steam shovels.The toys I seem to remember were similar to these. They were supposed to be construction machines of the future: larger, fancier, and more exotic than their contemporary cousins. They were big, and therefore expensive, which is why I knew I'd never convince Mom and Dad to buy me one. I estimate they were some 12 to 18 inches in height and length, but I'm remembering their scale as seen by a kid, so they could have been bigger.

I haven't retained detailed pictures of these machines. Rather I have impressions of how they looked. One feature was an exaggerated vertical scale; that is, the cab section of a futuristic steam shovel would be two or three times as tall as a real one. Second was an enormous overall scale. Though the toys were roughly the same size as their realistic counterparts, details like their cabs were scaled such that the machine appeared to be several stories tall. I remember streamlining and futuristic crisp edges, like American cars of the post-fin era. However (as you'll see below) this impression conflicts with the art-deco styling in images that "resonate" in my memory. I also have a vivid impression of lots of wheels. Not the big, fat wheels like on the realistic toys, but many small ones. Where a real tractor would have one big wheel at each corner, the futuristic tractor sported a housing grouping together perhaps a dozen small ones. Oddly, the strongest impression I've carried for all these years is of the "glass" used for the cab windows: a vivid turquoise plastic that to my young mind seemed indescribably exotic, the very essence of the future.

Three or four times in my adult life I've encountered images which remind me of these wonderful machines. None of them evoke a "that's it!" reaction. Rather they stir old memories, tantalizing me without ever coming into focus. Two images with the strongest resonance come from Arthur Radebaugh's amazing series of advertising paintings for Bohn.

This one produces the strongest reaction. The scale, the many small wheels, the segmented steering unit, and the tiny glassed-in cab are much like I remember the toys having. The glass would be turquoise, of course, and the scale of the driver might be even smaller.

What resonates most in this one, apart from the mini-wheels, is the proportion of the cab area. Narrow and quite tall, with a streamlined canopy integrated into the body. The tall chrome grille also seems familiar.

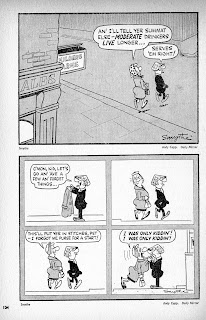

The last resonant image surprised me when I encountered it in one of Alden McWilliams' Tom Corbett comics. I didn't recognize the shape of the "water-manufacturing machine" so much as I did its scale and purpose. This is the sort of job my dreams toys were built to do. That rear-mounted scoop rings a bell, and something about the view of the machine in the final panel is tantalizingly familiar.

I've never met anyone who has heard of these toys. I've never found them in old ads, nor offered on ebay, nor described on baby-boomer toy fan sites. The more I research them the closer I come to concluding that the entire experience was imaginary. Maybe I saw ordinary toys which my memory transformed into things of magic. Or perhaps I saw one of those Bohn ads and over the years manufactured the memory of seeing them as toys.

One thing I know for fact. The annual visit to the Sears Toyland was real, and the store definitely pulled out all the stops to fill their huge room with the most mouth-watering toys. Using several autobiographical guideposts I've determined that I would have seen these toys (if I did see them) sometime between 1959 and 1964, more likely earlier than later. In 1964 I entered high school and this is definitely a memory of my elementary school years.

So I entreat you to spread the word and establish for all time the truth or fiction of one of my childhood's fondest memories. Were the super-machines real?