How do I know I'm getting senile? Let me count the ways. Actually, there's only one way: the fact that in an earlier post I said I hadn't seen any Bruce Gentry dailies beyond the couple of tear sheets I presented...totally forgetting that I had two entire stories of Ray Bailey's postwar aviation strip!

Only they aren't really Bruce Gentry. They're adventures of Alain Carter, Pilote Detective, in photocopies given me a dozen or more years ago by famous French comic artist and fine gentleman, Gerald Forton. I had entirely forgotten them. Yesterday, in another excavation through my garage inspired by reading everyone else's blogs, I stumbled upon the envelope. Gerald worked at DiC Animation at the same time I did. We often chatted about our favorite classic comics, French and American. Gerald was another Ray Bailey enthusiast, and he xeroxed these samples from French reprint comics.

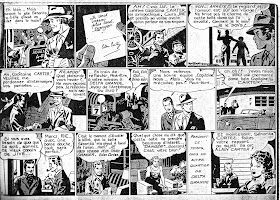

I have 22 pages in all, comprising two adventures. The dates were removed, of course, but they apparently start at the strip's beginning. We're introduced to Bruce's future sidekicks: South American romantic Ricardo and comic relief hep-cat Jive. Both keep their original names in the French version (though I'm sure Jive's name is pronounced Zheev). I think Jive is supposed to be a South American Indian. He got his nickname when he returned from a visit to the States obsessed with swing music and speaking jive lingo.

I have 22 pages in all, comprising two adventures. The dates were removed, of course, but they apparently start at the strip's beginning. We're introduced to Bruce's future sidekicks: South American romantic Ricardo and comic relief hep-cat Jive. Both keep their original names in the French version (though I'm sure Jive's name is pronounced Zheev). I think Jive is supposed to be a South American Indian. He got his nickname when he returned from a visit to the States obsessed with swing music and speaking jive lingo.Bruce Gentry was an attempt to reinvent the fly-guy adventure strip to fit a postwar world. Unlike Steve Canyon, which launched the next year, the war and the military didn't play a part in the strip. Bailey wanted to start with a clean slate. This teaser ad from July 1945 makes that point outright in the final sentence. Odd that they reveal that sexy Eden Cortez works for a spy--that was supposed to be a surprise for week two! (Sidebar: it strikes me funny that in 1945 they say Caniff is famous for "Male Call." Terry who?)

Bailey's complete command of his drawing is apparent from the outset. Gone are the uncertainties of his Vesta West days. Ray learned well during his years with Caniff. Characters, backgrounds, and staging are slick and thoroughly professional. His style would evolve further. For one thing, he hadn't settled on his standard "good guy" face. For another, he plays the scenes mostly in close-ups and medium shots; in comic books he would begin using more full-figure shots. In the absence of the original strips, I want to retranslate these into English and post an entire story for other Baileyphiles. Stay tuned!

One question gnaws at me. Why does the letterer put the characters' names in ALL CAPS? Is this one publisher's idea or was it commonplace in French comics? I'm reminded of how DC comics used to put a hero's name in boldface each time it appeared. I grew up reading comic balloons "aloud" in my head, and to me boldface meant a word was spoken louder. So people in DC comics talked funny. I could accept, "Look! It's Superman!" but not, "Come right in, Superman!"

Come to think of it, certain writers used boldface in odd ways. One way to recognize Paul S. Newman's work is that he'd boldface "not" and "don't" even if it didn't make sense in context: "You go to bed, dear. I'm not sleepy yet," or "This is his car but I don't see him anywhere." Jack Kirby had a similar thing for "not." Harold Gray would boldface (or rather, underline) so many odd words that rumors popped up saying he was sending some kind of coded messages!

No comments:

Post a Comment