I've been digging through my garage looking for this item for months. Finally my labors have borne fruit.

I mentioned in an earlier post that I'd done comic-style artwork for an episode of the TV series Remington Steele. One of the props in that show was a fake newspaper comic section. Remington and Laura are fans of "The Blaster", an adventure strip supposedly produced by curmudgeonly cartoonist Raymond Kelly, but actually ghosted by his murderous assistant, Arte Wayne. Among the art I produced was a Sunday episode (in black and white) which presented the show's opening action in comic form.

The Sunday episode art was inserted into a mockup comic section that the post-production house had lying around. The post house was the Howard Anderson Company, a legendary post-production and effects company that has been around since 1927. It goes without saying this mockup had been around a l-o-o-o-ng time...no one remembered just how long. Whenever a client needed a phony comics section, Anderson stuck new art into an empty space on the mockup and ran off a new four-page "edition."

I'm not sure exactly how they did this. These were the days before large-format copiers and computer printers. They either had an old-fashioned letterpress unit or an offset printer which they fired up for these special occasions. The copy I have doesn't have the "indentations" characteristic of letterpress printing, so I'm voting for offset. It had to have been a big machine: the fake paper is the same size as a full-sized American newspaper spread.

I was fortunate to get a spare copy of the Remington Steele edition. I present it here for two reasons: first, to give everyone a look at this comic oddity; and second, to invite you Golden Era art-hawks to tell me who drew the other features. I'm sure there are some interesting stories buried here.

Here's page one:

The first strip, "Our Street," has a 1950s UPA look to it. The strip isn't very slick and like several other features has no story. To me this implies it was made specially for the section and not taken from some cartoonist's back stock of unsold strips. Bill Carter is surely an alias.

The second strip, "Casey the Cop" by Wally Bullock (another alias?), seems amateurish to me. Or is it just "stylized"?

The third strip, "Donny and Dolly Dewlap" could conceivably have been someone's unsold strip. It delivers a gag rather than being open-ended like the last two. 'Ted Baker' is too generic to take seriously.

The fourth feature, which has no title, is drawn in a capable early-1930s adventure style reminiscent of "Tailspin Tommy". The signature is interesting: 'Jan Grippe' is unusual enough to be a real name. Google turned up two references to a 1950 movie producer with this name, but I couldn't find the pages. Then there was a Jan Grippo (b. 1906) who co-produced the Monogram "Bowery Boys" movies. The sig could be "Grippo." Maybe he started out as an artist and tried to sell a daily adventure.

The last strip, "Captain Smith", is drawn in a competent 1940s semi-realistic style...except for the main character, who is Dick Tracy under another name. Though the episode has a beginning and an end, it doesn't seem like an unsold daily. "K. Lentz" means nothing to me. IMDB didn't have any Lentzes that made sense, and the name was too vague to make a meaningful Google search. The lettering on this strip is the most professional of the bunch; it has almost a Ben Oda look to it.

And now page two:

"Uncle George" by 'Max Morgan' (surely a fake name) could be from almost any time. My guess is 1950s. The art isn't exactly bad, but it ain't great either.

"A Day at the Fair" by 'Todd' is completely unlike any other strip in this potpourri. Whoever this guy is (the signature 'Michael Kent' sounds unlikely), he must have trained as a 1930s animator. Both character design and drawing style point that way. It's a damned nice job, too.

Look who's here! "Toby" is by none other than animator extraordinaire T. Hee (real name Alex Campbell). He signed his own name and got a byline. Among his many employers was UPA (early 1950s). Given the style of "Our Street", could there be a UPA connection to this paper? Or am I grasping at straws?

"Marty" by 'Herb Klynn' appears to have been drawn by a cartoony artist drawing straighter than usual. Something about it says late-1940s to me (could it be Marty's resemblance to the Bardahl man?).

"Snips and Runty" seems to be the top row of a real (unsold) Sunday page, although the signature is probably phony. Unlike most of the strips here, the lettering appears to be professional.

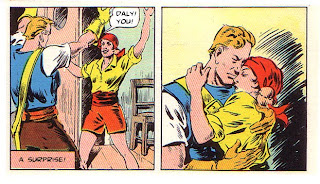

"The Rovers" intrigues me. Based on both the cartooning style and the heroine's dress and hair, I'd swear this was an unsold strip from the late 20s or very early 1930s. Its pacing suggests it's part of a longer story, and its subject brings to mind all those "Joe Palooka"-style strips. Google drew a blank on 'Leo Courey'.

Page three has a couple of features I know something about:

"Gerry" is likely the work of Gerry Woolery of Playhouse Pictures, the animation studio which contracted with the Steele team to supply art for the show. It was probably done on the spot to fill the hole to the left of "Sylvia Trace."

"Sylvia Trace" is, of course, two retouched "Dallas" dailies over which I lettered new dialogue. This was from my latter days on the project, when the late Thomas Warkentin was brought on as inker. You don't need a very keen eye to recognize J. R., Pam, Bobby, and Miss Ellie under those mustaches and glasses. Gerry agreed to my leaving Thomas' and my names on the strip, since Playhouse Pictures got screen credit for the Steele art, not me.

"The Blaster" is the fake Sunday I drew. Of course I signed it 'Raymond Kelly', but using my own signature style. Some friends who saw the episode thought I'd actually signed my own name to the art.

"Dinky" seems to be signed 'Ade'. It appears to be newer than most of these strips. It has that light, casual style that started in the 60s and continues to this day.

The fourth page of the mockup merely repeats the strips on page two. Now listen up, art spotters and strip historians. Who drew these strips? When? Why? Has anyone out there seen this comic section in other TV shows or movies? Get to work! And thanks.