In the last post I presented some of the newspaper strips showcased in the British Cartoonists Album. Today we'll see the rest of them.

First off is Jack Dunkley's The Larks. This domestic strip ran from 1957 through 1984. The versatile Dunkley also drew editorial cartoons, sports cartoons, and cooking and gardening strips. According to the British Cartoon Archive The Larks was originally written by Bill Kelly and Arthur Lay. Later writers included Robert St John Cooper, Brian Cooke, and Ian Gammidge. The Larks were a working-class family (the dad worked in a supermarket), but according to the BCA, when Cooke began writing the strip in 1962 he upgraded them to middle class.

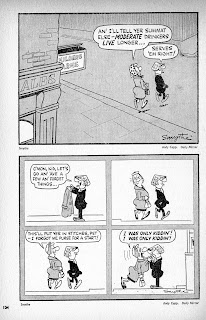

Here's another interesting strip I'd never seen. An article in the Daily Mirror calls The Flutters "a sports-page strip about a couple who liked to gamble (hence the title)." Can someone explain what "flutter" has to do with gambling? Anyway, I really enjoy Len Gamblin's artwork here, and the story is funny. It turns out The Flutters was written by Ian Gammidge, a cartoonist who served as staff writer on many Mirror strips, including The Larks. This obituary for Gammidge details the many projects he worked on.

It's on to the adventure strips now. Leading the pack is Buck Ryan, a tough-guy detective strip Drawn by Jack Monk and written by Don Freeman. According to Lambiek.net, in 1937 Monk and Freeman were working on a strip adaptation of an Edgar Wallace story when rights problems killed the project. They decided to create their own strip, and Buck Ryan was the result. The strip ran until 1962, so it was on its last legs by the time the Album came out. I read somewhere that Ryan was conceived as an "American-style" strip. The tough atmosphere and high body-count suggest this may be so, but I don't know if it's true. Monk's art improved greatly over the years--check out this blog entry about the first Buck Ryan story.

Garth, the time-traveling muscle man, debuted in 1943 and ran until 1997. Apparently it was co-created by artist Steven Dowling and BBC producer Gordon Boshell. Dowling wrote part of the first story, then Don Freeman was brought on board. I know Peter O'Donnell wrote some later episodes; there were probably others. The strip had a rather convoluted storyline in its earlier days, which is described here. The Lambiek biographies of Steven Dowling and his assistant John Allard conflict. One says Allard took over the artwork in 1957; the other says Allard began assisting in 1957 and took over completely in 1968. In 1971 he relinquished the art chores to Frank Bellamy. The art on Garth still confuses me. Dowling's earlier strips which I've found online are drawn in a "mainstream" style quite unlike the highly stylized work below. But this is the style in the last dailies before Bellamy took over. Could Allard have drawn this example? I don't know. Opinions vary about Garth's changing art style. Frankly I don't like this one much. I preferred Bellamy's dramatic art, even though his Garth was ridiculously over-developed. On the other hand, by the time Bellamy took over the strip had dropped any semblance of an underlying storyline. The continuities I read in The Menomonee Falls Gazette simply dropped Garth into one exotic world after another and gave him another naked woman to nail.

Last and certainly not least we have Romeo Brown, the skirt-chasing private eye. As I mentioned in the last post, Alfred Mazure was the original Romeo artist. When he moved over to Jane, Daughter of Jane, his assistant Jim Holdaway took over. Peter O'Donnell wrote the scripts. I'll never quite understand Romeo Brown, an almost completely asexual strip about leering sex. Holdaway had a strong comic flair, but in these strips you can see his realistic side straining to escape. He found release the following year in Modesty Blaise.

One post remains from the British Cartoonists Album. Next time, political and gag cartoons.

4 comments:

Great article and review of the strips.

Allard assisted Dowling and did take over from him on the art chores but he also annoyingly continued on Garth with FB. Bellamy wanted to reduce Allard's involvement on his artwork (see those stupid 'dashes' as clouds and the waves on the sea in early FB stories), which detracted from Bellamy's artwork. See my

blog entry on FB explaining Allard's involvement on Garth while FB worked on it

And lastly you asked about 'flutter' as an expression....

The OED says:

"1874 Hotten's Slang Dict. (rev. ed.)‘I'll have a flutter for it’ means I'll have a good try for it." and now means mostly having a bet or wager. I always understood it as an excitement - think fluttering of bird wings

Thanks for the kind words, Norman.

Back in the day I wondered about those dashes in the sky. At the time I speculated that an editor had asked Bellamy to follow Allard's style for a while to ease the transition...they did that all the time in American papers. I figured the dashes were Bellamy's nod to his predecessor. Guess I was wrong...

Reg Smythe's Andy Capp began as a single-panel cartoon in 1957 and switched to strip format. Both versions are shown in the Album. Andy Capp has been an international phenomenon and is still running today. Obviously it's a flaw in my character, but I've always found the strip repellent.

You're not the only one. I will say the earlier strips seem more interesting to me art-wise given the perspectives in the backgrounds versus the flat approach Smythe went with in the end. My city ran Andy Capp for many years but I haven't seen it printed locally for several decades. I don't suppose I miss much, but they do use his image to sell a snack bag called "Hot Fries" (and other flavors).

Nice to see you found Buck Ryan too. I am writing a series of articles for Rick Marshall's new Nemo about comic strip and comic book artists directly influenced by Milt Caniff or working for them. It seems that Jack Monk was one of the first to pick up on those influences, with his first strips looking even more like Sickles than Caniff. The name Buck Ryan could be influenced by Pat Ryan.

Post a Comment